2019 marks the end of the Airbus-Boeing duopoly

For almost 20 years now, the Airbus-Boeing duopoly has shared almost the entire airliner market. But a trend favorable to Airbus has quietly settled in recent years. In this text, we will examine how the MAX saga will accelerate this trend and put an end to the Airbus-Boeing duopoly.

The battle for orders

For the past few years, we have witnessed a mad rush inside the Airbus-Boeing duopoly. The goal is to succeed in establishing itself as the world’s leading manufacturer of airliners. To achieve this, the two protagonists also fought a merciless price war.

From 2010 to 2015, the price reductions had a significant impact on aircraft sales. Over this short six-year period, the Airbus-Boeing duopoly garnered nearly 14,100 firm orders. The A320neo and 737 MAX promised fuel savings of 20% when the price of oil was very high. At that time, the two giants offered their new single-aisle aircraft at very competitive prices. The airlines simply succumbed to the tempting offers of the two aircraft manufacturers.

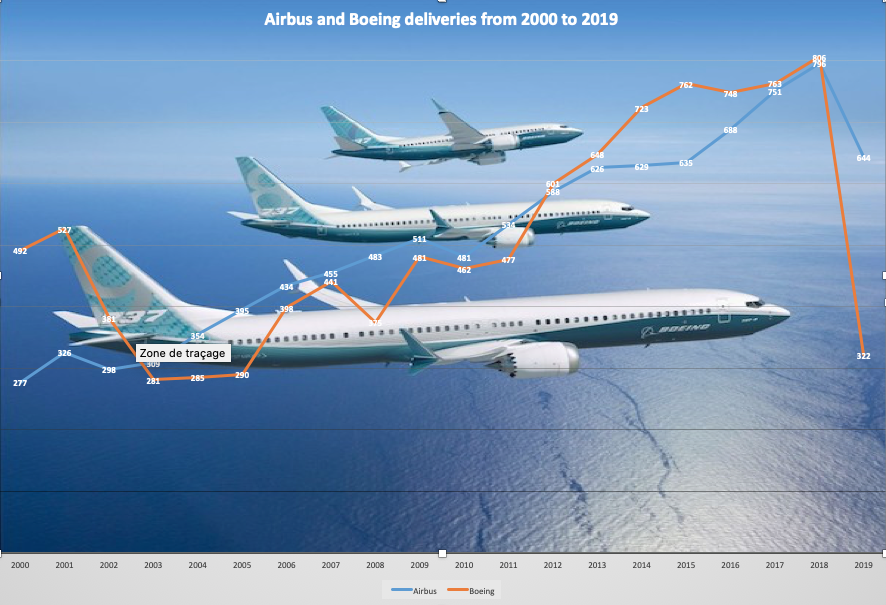

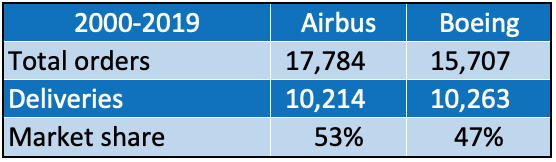

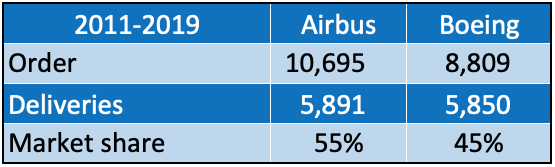

Here we have compiled the data available* on orders and deliveries for the Airbus-Boeing duopoly for the period 2000 to 2019. We present them on the following two graphs:

The order graph clearly shows a peak in orders for the period 2010-2015. It was also in 2010 that Airbus started to be on top of Boeing in terms of orders. But looking at the deliveries, we realize that the race is much tighter.

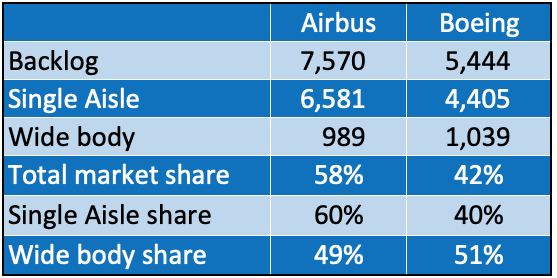

We have then summarized the important information in three tables:

The figures speak for themselves, in 2019 Airbus holds 58% of the backlog.

MAX deliveries in 2020

It is now known that the MAX will not return to service before mid-February 2020. The slightest hitch will further delay its return to service. American Airlines has already postponed the resumption of MAX flights until April 7. Air Canada, Delta Airlines and United Airlines can reasonably be expected to do the same in the coming days. But you have to remember that this scenario remains the most optimistic.

On the two previous graphs, 2019 marks a clearly visible break. In our opinion, the low level of orders and deliveries at Boeing will continue in 2020 and 2021. It is still very difficult to predict how Boeing will emerge from this crisis beyond 2021. But for the next two years, the possible scenarios clarify themselves.

Taking into account the obstacles to overcome, the return in service of the MAX would be at the earliest for the second half of 2020. But other delays could be added. The new flight computer programming, particularly that relating to MCAS, could cause unexpected problems.

The FAA recently withdrew Boeing’s privilege to issue the certificate of airworthiness for MAXs already produced and ready for delivery. It is therefore the FAA itself which will now carry out the final inspection of each aircraft before delivery to a customer.

Boeing uses an army of engineers to determine the airworthiness of aircraft before delivery. In contrast, the FAA only has a handful of engineers and technicians to do the same job. The FAA may say it will not slow delivery, no one believes it. Note that this would be a great tactic if the FAA wanted more money to hire more staff.

MAX production halt

Boeing planned to increase the MAX production rate from 52 to 57 aircraft per month in the summer of 2019, but in April it announced a reduction to 42 per month. The company then planned to return to 52 per month as soon as the flight ban was lifted and then to 57 in the following months. But last week, Boeing confirmed that the production rate of 57 a month is postponed to 2021.

What is particularly astounding about the turn of events is that earlier Boeing had asked its suppliers to maintain a rate of 52 units per month. However, the largest and largest supplier of the MAX, Spirit Aerosystem is currently left with 90 fuselages not delivered in storage. As a result, the company must now pay its employees an additional three days of vacation for the holiday season. The excess inventory explaining this extended leave. But when they will come back to work in January, this surplus will still be huge and will continue to grow.

For its part, the engine manufacturer CFM must currently have an inventory of about 180 engines ready for delivery. The suppliers of MAX and their employees therefore seem to be the forgotten ones of this crisis.

As can be seen, Boeing’s decision to maintain the rate at 52 units per month among suppliers has serious consequences. There is now an inventory of 737 MAX in spare parts stored at supplier’s expense. For parts and systems already produced, employees and suppliers must be paid.

The announcement of a major slowdown or a complete halt of the MAX production will have significant financial repercussions. Delaying the decision only makes the situation worse.

MAX’s order book

MAX’s order book now stands at 4,405 units and Boeing likes to remind it to financial analysts. But you have to be very naive to believe that the Chicago company will deliver all of these aircraft.

For example, Jet Airways alone has 217 MAX on order. However, this Airline stopped operating on April 17 when the MAX was already grounded. Boeing is therefore left with MAX in the colors of Jet Airways which will therefore not be delivered. Then there is Norwegian who is having serious financial difficulties and who has 100,737 MAX on order. Even if the company survived until the MAX returned to flight, it is far from certain that it will then be able to accept deliveries.

Next are leasing companies that failed to place some of their aircraft before the ban. Before the crisis started, this number was higher than normal. The aircraft produced during the stoppage of deliveries and not placed yet could prove to be very difficult to place. To land its last orders for MAX, Boeing was forced to make very large discounts. The price that airlines are willing to pay for a MAX today has dropped significantly. Landlords will end up with rent that will not cover the cost of the purchase. To this must be added the drop in the residual value of the MAX which will further increase the charges.

Several leasing companies are therefore at risk of declaring bankruptcy in the next two years. Some orders from these companies will be lost forever.

Passengers acceptance

The history of civil aviation has had many dark episodes, but nothing compares to that of the MAX. The number of aircraft grounded and the length of the ban remain unmatched. But the most damaging part is the number and frequency of revelations, each more disturbing than the other.

Boeing’s name has been drag in the mud for almost 10 months now. Boeing may make all the declarations and demonstrations it wishes about the safety of the MAX. No one believes them anymore, the credibility of this company is now at its lowest.

The episode most similar to the MAX was that of the McDonnell-Douglas DC-10 in May 1979. The DC-10 had been banned from flying for 49 days following the Chicago crash that claimed 271 lives. The airline involved at the time was American. The first DC-10 that took off from Chicago after the ban was lifted had only 100 passengers on board. To attract them, United airlines then offered its tickets at very low prices.

Six months after the lifting of the flight ban, load factors on the DC-10 had returned to normal. However, all airlines had been forced to significantly reduce the tickets price on the DC-10. The plane was flying, but it was clearly in deficit for the airlines. Over the following years, the DC-10 was phased out of service by airlines.

China

China is one of the fastest growing emerging markets in civil aviation. This market now accounts for almost 10% of global demand for airliners, and this proportion is expected to double by 2030. But the Chinese market is very atypical, every aircraft orders having to be approved by the government. And the latter expects big Western companies to invest and do technological transfer to China.

It is for this reason that Airbus installed an A320 assembly line in Tianjin in 2008. Airbus has just announced an increase in production from 4 to 6 aircraft per month.

For its part, Boeing has only opened an interior finishing center for the MAX. In 2016 and 2017, Boeing’s orders from China suffered a 70% drop. Since the start of 2018, Boeing has not received a single firm orders from China. The current trade war between China and the United States does nothing to resolve this issue. The American government still refuses to give in on the issue of investments and technological transfers.

The absence of Chinese orders has forced Boeing to reduce production of the B787 from 14 to 12 aircraft per month. This slowdown will be effective in the fourth quarter of 2020. Unless the American aircraft manufacturer changes course, the Chinese market is now closed to it. The revelations of the past 10 months only strengthen the determination of the Chinese government in its decision. China could thus help to upset the balance of the Airbus-Boeing duopoly.

The end of the Airbus-Boeing duopoly

It is unrealistic to believe that the production of the MAX will return to 52 aircraft per month. In addition, the return to service of the MAX will probably be the last lap of the B737 and it could be a very short one.

The Airbus-Boeing duopoly has so far played a decisive role in the development of civil aviation. But we are witnessing a paradigm shift today, as Airbus will soon take control of the single-aisle market. This market represents more than 80% of sales for Airbus and Boeing.

Because the A320 is younger, contains more recent technology and is in its first iteration, it has passed more easily through the latest re-engine. By adding the A321LR and XLR, airbus has managed to gain the upper hand over Boeing, which has nothing to offer. Once the trend was established, it remained for Airbus to gain the upper hand in deliveries over Boeing. The 737MAX’s ban was the event that enabled it to secure its monopoly. Boeing will take at least five years to start taking catching some of the lost ground to Airbus.

With the Airbus-Boeing duopoly now a thing of the past, stakeholders in the aeronautical and air transport industries now have to change their analysis grids. The time has come to accept and adapt to the paradigm shift.

The next text on this topic will be entitled: Decision time for Boeing

*Our main data source was Decision Analytics from Airinsight Data Service

>>> Follow us on Facebook and Twitter